Must Know guide

What Is Active Recall?

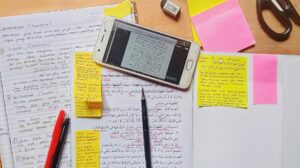

Active recall is the practice of actively stimulating memory during the learning process. Instead of passively reading or highlighting text, you close your books and try to remember what you’ve just studied. This forces your brain to retrieve information from memory, strengthening neural pathways and improving long-term retention.

Most students spend their time on passive learning activities—reading, highlighting, and re-reading notes. These activities create familiarity with material but don’t build strong memories. Active recall flips this approach by making retrieval practice the primary learning activity.

Research consistently shows that students who use active recall outperform those using passive study methods, often by significant margins. The technique works because it mirrors how you’ll actually use the information—by pulling it from memory when needed.

The Testing Effect

Active recall leverages the testing effect, one of the most robust findings in cognitive psychology. The act of retrieving information from memory strengthens that memory more than simply reviewing the information again. This happens because retrieval practice requires more cognitive effort than recognition.

When you read text, you’re using recognition memory—you see the information and feel familiar with it. But on exams and in real-world applications, you need recall memory—the ability to bring information to mind without external cues. Active recall specifically trains this crucial skill.

The testing effect occurs even when you answer questions incorrectly. The act of searching your memory for information, even unsuccessfully, creates learning benefits. This is why difficult, desirable difficulties in learning often produce better long-term outcomes than easier methods.

Implementation Strategies

Question Generation: After reading a section of text, close the book and write down everything you can remember. Then, create questions about the material and try to answer them from memory. This two-step process combines free recall with cued recall practice.

Flashcard Systems: Create questions on one side of cards and answers on the other. Focus on concepts, relationships, and applications rather than simple definitions. Test yourself regularly, paying special attention to cards you find difficult.

Blank Page Method: Start with a completely blank page and try to recreate key concepts, diagrams, or formulas from memory. This reveals gaps in knowledge that passive reading might miss. Use different colors or drawing styles to make the process more engaging.

Teaching Others: Explain concepts to friends, family members, or even imaginary students. Teaching requires you to retrieve information and organize it coherently, providing excellent active recall practice while revealing areas that need more work.

Optimizing Question Design

Effective active recall questions require careful construction. Avoid questions that can be answered with simple yes/no responses or single-word answers. Instead, create questions that require explanation, analysis, or application of concepts.

Good Question: “Explain how photosynthesis converts light energy into chemical energy, including the major steps and molecules involved.”

Poor Question: “Does photosynthesis use light energy?”

Use cloze deletion—sentences with missing words or phrases that you must fill in from memory. This technique forces you to understand context and relationships between concepts, not just isolated facts.

Example: “The process of _____ converts _____ energy into _____ energy through reactions that occur in the _____ of plant cells.”

Spacing and Timing

Combine active recall with spaced repetition for maximum effectiveness. Review information at increasing intervals: after one day, three days, one week, two weeks, and one month. This spacing takes advantage of the forgetting curve to strengthen memories just as they begin to fade.

Use active recall during initial learning sessions, not just for review. After reading each paragraph or section, pause and try to recall the main points. This immediate retrieval practice helps transfer information from working memory to long-term storage.

Schedule regular active recall sessions separate from passive reading time. Many students try to combine these activities, but active recall requires focused attention and mental effort that’s difficult to maintain while passively consuming information.

Subject-Specific Applications

Mathematics and Sciences: Practice solving problems from memory before looking at solutions. Try to derive formulas or explain step-by-step processes without referring to examples. Create concept maps showing relationships between different topics.

Languages: Practice speaking and writing without looking at references. Try to recall vocabulary, grammar rules, and sentence structures from memory. Use the target language to explain concepts you’re learning in other subjects.

History and Social Sciences: Create timelines from memory, explain cause-and-effect relationships, and analyze historical events without referring to source materials. Practice writing essay outlines from memory before consulting notes.

Literature: Summarize plots, analyze themes, and quote passages from memory. Explain character motivations and literary techniques without referring to the text. Connect different works and authors through recalled knowledge.

Overcoming Common Challenges

Initial Difficulty: Active recall feels harder than passive reading because it requires more mental effort. This difficulty is a feature, not a bug—the challenge indicates that learning is occurring. Embrace the struggle as a sign of effective practice.

Time Investment: Active recall initially takes more time than passive reading, but it saves time in the long run by creating stronger memories that require less review. The upfront investment pays dividends during exams and practical applications.

Confidence Issues: Many students avoid active recall because they don’t want to discover what they don’t know. Reframe these gaps as opportunities for targeted improvement rather than failures. Not knowing something is information that helps you study more effectively.

Measuring Progress

Track your active recall performance to monitor improvement and adjust your study strategies. Keep records of which questions or topics you find most challenging, and spend extra time on these areas.

Accuracy Tracking: Note which questions you answer correctly on first attempt, second attempt, or not at all. This data helps you identify patterns in your learning and optimize your study schedule.

Speed Improvement: Time how quickly you can recall information accurately. As memories strengthen, retrieval becomes faster and more automatic. This fluency indicates genuine learning rather than temporary memorization.

Transfer Testing: Periodically test yourself on applications of knowledge rather than just memorized facts. Can you use concepts to solve new problems or explain novel situations? This transfer ability indicates deep, flexible understanding.

Combining with Other Techniques

Active recall enhances other learning strategies when used systematically. Use it with the Feynman Technique by trying to explain concepts from memory before checking your understanding against source materials.

Combine active recall with interleaving by mixing questions from different topics during practice sessions. This combination builds stronger discrimination skills and prevents over-learning of individual concepts at the expense of broader understanding.

Use active recall to identify gaps that need attention during spaced repetition sessions. Questions you consistently miss deserve more frequent review, while easy questions can be spaced further apart.

Creating Effective Study Groups

Active recall works excellently in group settings when structured properly. Take turns asking each other questions, explaining concepts, and solving problems from memory. The social pressure and multiple perspectives enhance the learning experience.

Avoid study groups that devolve into passive reading or socializing. Structure sessions around active recall activities with specific goals and time limits. Each member should come prepared with questions and be ready to participate actively.

Record group sessions (with permission) so you can review difficult concepts later. Often, explanations that make sense in the moment become unclear when you’re studying alone. Having recordings allows you to revisit these explanations during individual practice.